Over the past 50 years, adult education scholars have developed a robust literature on “andragogy,” the art and science of teaching adult learners. In the 1970s, Malcolm Knowles, a one-time head of the Adult Education Association of the United States, introduced the word on these shores (from the German for “man-leading”) to distinguish the facilitation of adult learning from pedagogy (child-leading), directing the learning of children.

Adult and independent learner strategies could be the next big driver of school improvement

Scholars have synthesized Knowles’s assumptions about how to best support adult learners in an andragogical curriculum model of learning. The six fundamental attributes of this model are:

- Resources: The adult learner’s experience becomes a rich resource for their own and other’s learning.

- Need to Know: Adult learners need a meaningful reason to learn something.

- Efficacy and Direction: Adult learners are increasingly self-directing.

- Readiness: Life tasks and problems drive adults’ readiness to learn.

- Orientation: Adult learners seek immediate application for their learning.

- Motivation: The adult learner is increasingly motivated by internal incentives and curiosity.

These core attributes apply to all adult learning contexts, from literacy programs to professional learning for educators and can help drive school improvement in new ways. Best practices for developing current teachers follow these adult learning principles. Surveys and research further show that professional learning is most effective when it is relevant to the learner (e.g., teacher, leader), directly applicable to their professional context, and shared within a network of practice.

Adult learning for school improvement

For schools to continuously improve, leaders need to direct district policies, resource allocation, and new uses of technology so that schools become centers for teacher and leader learning. Educators must have opportunities to learn from each other, mentor and be mentored, and grow together in a community of practice. (Dufour 2009, Davidson, 2023)

A 2022 report from the Learning Policy Institute, Developing Effective Principals: What Kind of Learning Matters? highlighted a similar need for school principals. In spite of increased access to content related to leading instruction, managing change, developing people, shaping a positive school culture, and meeting the needs of diverse learners, principals’ access to crucial job-based learning opportunities (e.g., internships, applied learning, mentoring or coaching) is still limited. According to the report, “Only 40% of principals reported having had an internship during their preparation that allowed them to take on real leadership responsibilities characteristic of a high-quality internship experience, and very few in-service principals reported having access to coaching or mentoring.”

School leaders are even more isolated than teachers. They are true “lone rangers” in their buildings. As an educator who has led a district, taught adult learning in education departments at several universities, and now provides training for school districts involved in Cognia’s accreditation and school improvement efforts, I have seen firsthand how the lack of networked support for leaders can limit success in school improvement.

All part of continuous improvement

To be successful, school improvement should be a team sport. Everyone needs a coach, and all the players must share a common vision of what the game is about and be open to new ways of helping each participant (e.g., adult, student) achieve better outcomes.

Cognia’s approach to continuous improvement can be used in connection with pedagogy, andragogy, and heutagogy (the administration of learning for self-managed learners) in the strategic planning process, which also needs to be taught with greater emphasis in university-based leadership programs.

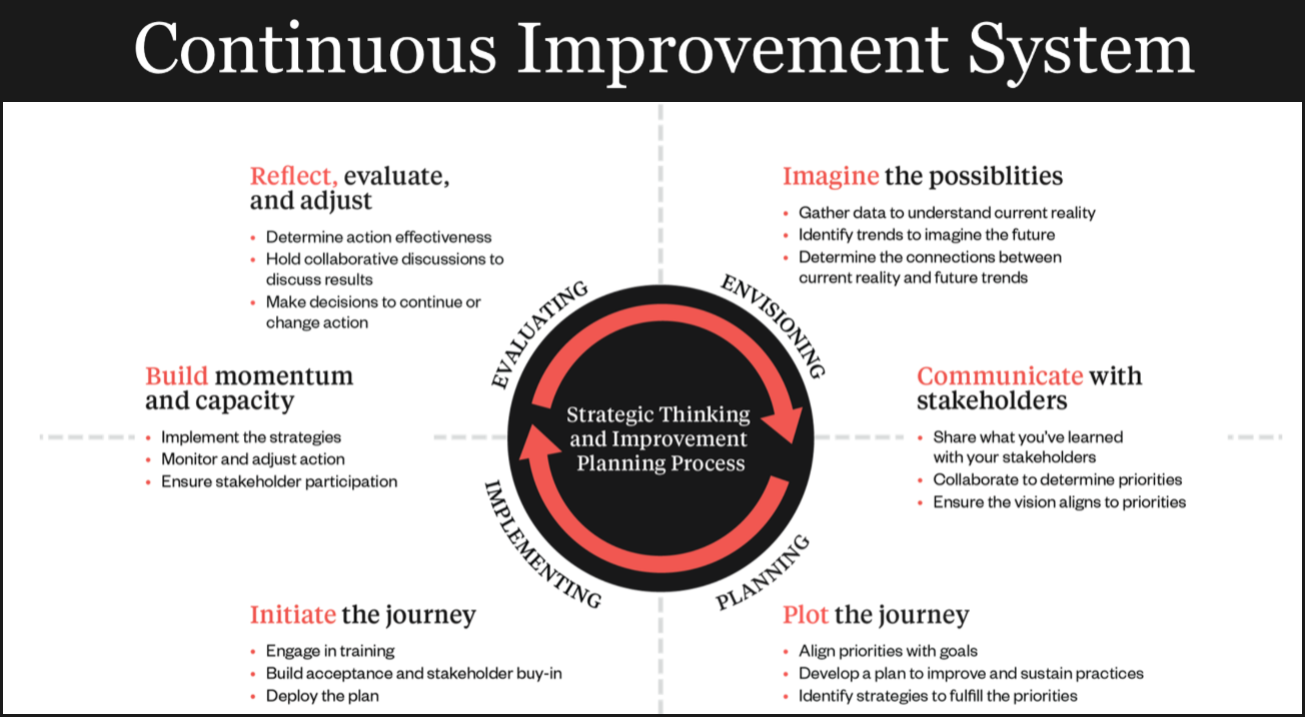

Cognia defines continuous improvement (Elgart, 2017) as “an embedded behavior within the culture of a school that constantly focuses on the conditions, processes, and practices that will improve teaching and learning.” The key dimensions of that work require four successive strategic actions (i.e., visioning, planning, implementing, and evaluation) that need to be revisited and repeated as a new cycle. For anyone interested, the best tool available for understanding what’s involved in this process is Cognia’s “inFocus guide for strategic thinking and improvement planning,” (2023) which should be a regular focus of every leader.

As shown in the chart below, the cycle begins with imagining the possibilities, communicating with stakeholders, plotting the journey, initiating the journey with training and fostering buy-in, building momentum and capacity, and reflecting, evaluating, and adjusting to begin the cycle again.

Unleashing andragogy and heutagogy to improve learning

To effectively educate adults, andragogy must be paired with heutagogy—the administration of learning for self-managed learners. In my work with schools and districts, to identify root causes of low performance across all dimensions of school quality, I see how indispensable andragogy and heutagogy are to the future of our education system.

The following chart identifies key principles of heutagogy in addition to pedagogy and andragogy.

Pedagogy |

Andragogy |

Heutagogy |

|

| Learner dependence | Dependent | Independent | Interdependent |

| Learning resources | Driven and controlled by teacher | Controlled by teacher and learner | Provided by teacher and learner, learner negotiates path |

| Learning reasons | Achieving next level | Improving performance | Developing potential; unplanned, non-linear |

| Learning focus | Subject-centered, prescribed | Task-or problem-centered | Proactive and problem-oriented |

| Motivation | External | Internal | Driven by self-efficacy |

| Teaching role | Process designer, imposer, knowledge holder and director | Facilitator, collaborator | Capability builder |

Young, S. (2018, March 7). Heutagogy: the art of self-directed learning. Acts of Leadership.

The old focus on traditional pedagogy, in which dependent learners follow external motivations and a prescribed curriculum to get to the next level and are directed by teachers who manage the process of learning and hold the knowledge that needs to be changed to usher in a new era of active, student-directed learning. While this approach can be useful for younger students, it cultivates the kinds of passive learning that are better suited for the industrial era rather than the digital age, where students learn more independently than in lockstep with each other. The pedagogical model needs to be changed to usher in a new era of active, student-directed learning.

The pedagogical model needs to be changed to usher in a new era of active, student-directed learning.

What will a new system look like? Teachers will be collaborators and active co-constructors of learning, optimizing support for each student. Learners will make choices in how they learn, helping to design their own learning experiences and pathways and progressing through content as they demonstrate competence in projects that engage with communities outside the school.

Taking adult learning to heart, we can create new ways for teachers to learn from one another and address the problems of practice, allowing them to be propelled by teachers’ intrinsic motivation and aided by expert peers who serve as facilitators and collaborators.

The areas needing improvement indicate that focusing on andragogy to improve adult learning for teachers and leaders can help shift the focus to student needs and experiences. It can also encourage teachers to conduct research to make improvements and begin the transition to a heutagogic system that will shift teachers’ roles and encourage self-directed and self-paced learning.

Looking ahead

When we have changed from policies that direct where and how long students must learn to an approach that allows them to learn where and how fast they can, we will be ready to create a system of learning through heutagogy. In the future, students will work with their teachers to create their own unique courses of learning—to go as far and as fast as they can on an unplanned, non-linear journey of exploration and discovery.

We can encourage students to set goals that are meaningful to them, draw on the passions and interests that drive them to learn, focus on knowledge domains (not subjects and courses), and develop the skills to become lifelong learners. Ultimately, we must ensure that all students have agency and can equitably achieve 21st -century learning goals at the pace appropriate for their learning. Only then will our education system be as powerful as our students can make it.

References

Cognia (2022), Performance Standards K–12 and Postsecondary Institutions, Performance-Standards.pdf

Cognia (2023), inFocus: A guide for strategic thinking and improvement planning, inFocus Guidebook

Cox, Elaine (2015), “Coaching and Adult Learning: Theory and Practice,” New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, chapter 3, Wiley Online Library

Darling-Hammond, L., Wechsler, M. E., Levin, S., Leung-Gagné, M., & Tozer, S. (2022). Developing effective principals: What kind of learning matters? [Report]. Learning Policy Institute. https://doi.org/10.54300/641.201. Updated September 14, 2023. Revisions are noted here.

Davidson, Scott (Spring 2022), “Get More Out of Professional Learning,” appearing in Cognia, The Source, Get More Out of Professional Learning – Cognia – The Source

Dufour, Rick (Fall 2009), Professional Learning Communities: The Key to Improved Teaching and Learning, appearing in Cognia, The Source, Professional Learning Communities: The Key to Improved Teaching and Learning – Cognia – The Source

Elgart, Mark A. (September 2017), Meeting the Promise of Continuous Improvement, Cognia White Paper, Meeting-the-Promise-of-Continuous-Improvement-White-Paper.pdf (cognia.org)

Eripuddin and Jufrizal (2021), JEE (Journal of English Education) Vol. 7 No. 1, June 2021, pp. 103-123, Eripuddin Jufrizal 2021

Gutierrez, Karla (2021), Three Adult Learning Theories Every E-Learning Designer Must Know, Association for Talent Development, 3 Adult Learning Theories Every E-Learning Designer Must Know (td.org)

Henschke, J.A. (2014) “Andragogical Curriculum for Equipping Successful Facilitators of Andragogy in Numerous Contexts” from the Selected Works of John A. Henschke, Ed.D. , Lindenwood, Henschke 2014

Holmes, Kathryn and Preston, Greg (2020), “Concept of Pedagogy and Andragogy Education” appearing in Community Medicine & Education Journal Vol 1 Issue 1 2020, Holmes Preston 2020

Patrick, Susan (Spring 2023), “Next Generation Accountability Systems for Student Success,” appearing in Cognia, The Source, Next Generation Accountability Systems for Student Success – Cognia – The Source

Rohlwing, Ruth L. and Spelman, Maureen, (2015) “Characteristics of Adult Learning,” Implications for the Design and Implementation of Professional Learning programs, chapter12, in Martin, L.E. Kragler, S, Quatroche, D.J., Hargreaves, A., and Bauserman, K.L., Handbook of Professional Development in Education, Successful Models and Practices, preK-12

Young, S. (2018, March 7). Heutagogy: the art of self-directed learning. Acts of Leadership. https://www.samyoung.co.nz/2018/03/heutagogy-art-of-self-directed-learning.html

© Cognia Inc.

This article may be republished or reproduced in accordance with The Source Copyright Policy.

The information in this article is given to the reader with the understanding that neither the author nor Cognia is in engaged in rendering any legal or business advice to the user or general public. The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this article belong solely to the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Cognia, the author’s employer, organization, or other group or individual.