Schools, districts, states, and their assessment partners—driven by an urgency to provide valuable, actionable information to educators and students that statewide summative assessments cannot alone provide—are increasingly focused on classroom assessment practices embedded in instructional activities.

For teachers, understanding what students know and can do requires teachers to navigate a broad array of assessment approaches, all of which are combined in so-called “balanced assessment systems” that provide opportunities for educators to:

- Verify learning of a specific unit of instruction

- Determine whether and how students are struggling with a concept

- Gauge student readiness for end-of-year (grade) summative testing

- Evaluate a year’s worth of learning

Ultimately these measures help determine if students have mastered grade-level content and are prepared for the next year of learning.

| Key Elements of Balanced Assessment Systems

The expansion of state-sponsored, statewide balanced assessment systems enable states, districts, and schools to monitor and inform learning progress throughout the academic school year. Typically, balanced assessment models include: Formative assessment, which gathers evidence of student understanding in real time through small, focused check-ins that support educators in making instructional adjustments Benchmark assessments, which are used at the end of a series of instruction to verify learning and identify students requiring additional instruction or enrichment. These assessments have a high impact on student learning and can support instructional decisions for each student and a class, school, or district. Interim assessments, typically offered in the fall, winter and spring, monitor student performance, progress, and growth through the year in reaching end-of-year academic goals to identify students or areas of learning that need attention. Through-year assessment does much the same thing but assess only those content standards covered in instruction during the learning period. Summative Assessments are end-of-year assessments that verify learning and fulfill accountability requirements. They provide aggregate information about achievement status and growth for use in program evaluation, policy decisions, budget allocations, and provide data on learning program and instructional effectiveness. |

Moving to a Student-Centered Paradigm of Learning

Even the most sensible balanced assessment approach can have its limitations, however. These types of measures are based on how well each student progresses in mastering prescribed content over the same time period when we know that young people learn in different ways and come to mastery at a different pace. Research also indicates that students learn more deeply and “own” what they learn by studying what captures their personal interests and connects to what they already know and aspire to become. In student-centered classrooms students view learning and instruction as personally relevant and engaging focused on local, culturally relevant context that authentically connects with their lives.

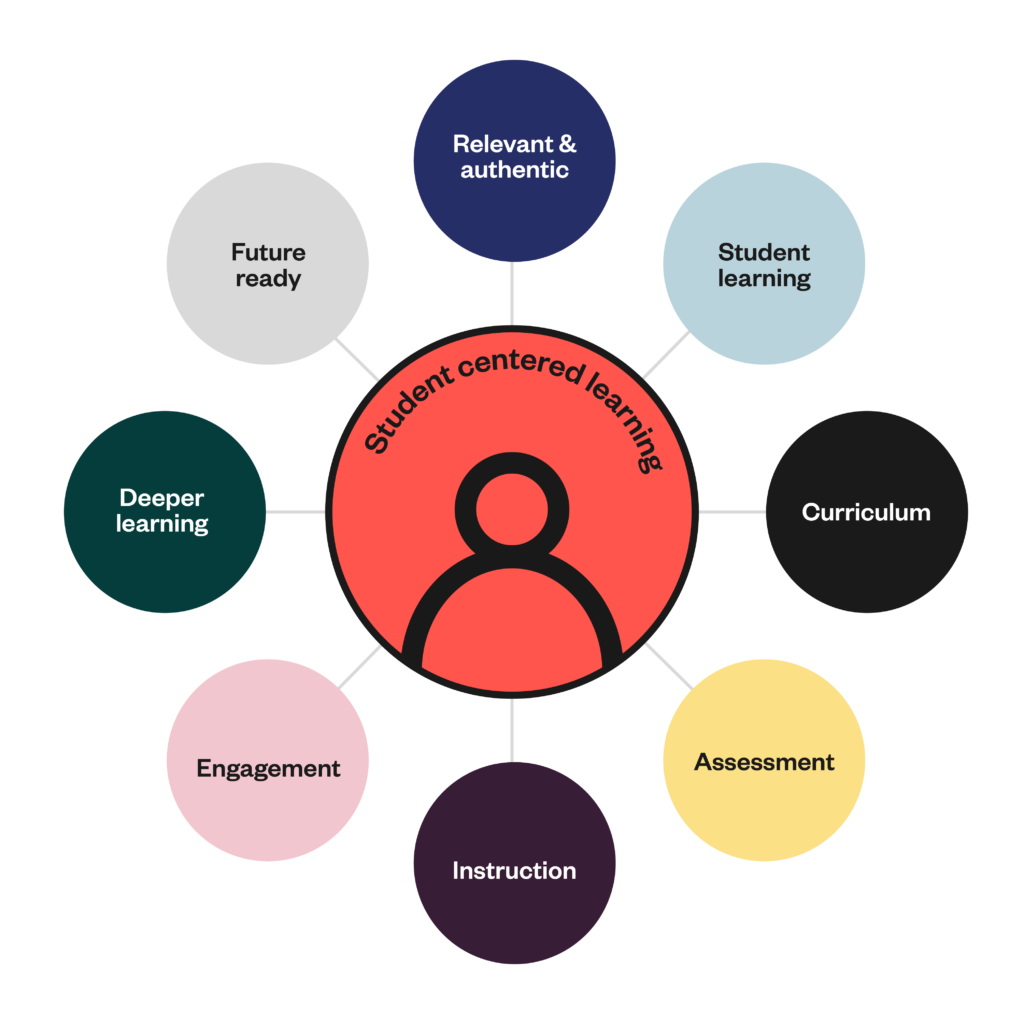

The future paradigm of student learning (see Exhibit 1. below) is designed to represent elements closest to students and their individual learning.

Future Paradigm of Student Learning

Exhibit 1. Future Paradigm of Student Learning

Assessment for a New Era

In the coming knowledge era, assessment will be geared much more to support teacher thinking and practices in the classroom that encourage active learning, student agency, and authentic ways of measuring what students do—making assessment more fully integrated into learning.

We will see more ongoing valuation of student progress toward achieving standards and classroom observations that create a comprehensive, student-centered view of progress. This approach will identify student learning and learning needs, embed assessment within lesson plans and curriculum units, and authentically engage students in their learning progress.

We will rely more on authentic assessment that requires students to apply what they have learned in unfamiliar, novel, or complex ways and often in real-word environments or situations that mimic the real world. Students will demonstrate learning by conducting research and writing a report, participating in debates, writing an essay about a book or chapter, conducting experiments, and other activities.

To increase the efficacy of student-directed learning, we need to change the dialogue about assessment from event- and pressure-based testing to thoughtful systems of assessment that use multiple measures to inform student progress against learning goals.

The impact of engagement

Student engagement is so important for students to direct their own learning, equally essential is to measure it. Student engagements survey can help measure:

- Behavioral engagement—a student’s participation in the life of the school as seen through effort, conduct, and participation.

- Cognitive engagement—how a student approaches academic tasks and promotes self-learning, including developing the ability to learn and development of self-regulating skills needed to be lifetime learners.

- Emotional engagement—a student’s feelings about school, staff, and peers.

Information from these surveys provides clues educators can use to improve the learning environment.

Advancements in assessment technology

New uses of technology now allow test makers to animate item stimuli and bring to life science phenomena (e.g., forces and motion) or dynamically manipulable stimuli (variables of motion and velocity) in a physics problem. Such methods can elicit knowledge and skills not measured from selected-response items on a test and are becoming more common in online interim and summative assessments.

We are also beginning to see the development of immersive environments for students to explore that can be incorporated into science content, embedded in unobtrusive formative assessments, and integrated into classroom units with immediate feedback. We also can conduct project-based learning and assessment activities online and will introduce game-based assessments in the next few years.

The advantages of building, storing, and evaluating student work samples for portfolio assessments enable educators to use portfolios in numerous ways to assess student projects, accomplishments, and growth, including for special education students and other non-traditional learners.

Assessment will use technology to assess higher-order thinking skills and will be tied to automated scoring enabled by machine learning and other artificial intelligence approaches to provide immediate, personalized, formative feedback.

From studies of interim assessments, researchers have developed a strong knowledge base that demonstrates the importance of immediate feedback to student learning, achievement, and motivation. In the future we can build applied uses of feedback to maximize student progress and motivation. Formative feedback identifies what students have mastered and partially mastered and their subsequent learning needs. Research indicates that formative feedback is the third-highest influence on student achievement among findings from the thousands of studies included in a meta-analysis of over 800 published meta-analyses.

To increase the efficacy of student-directed learning, we need to change the dialogue about assessment from event- and pressure-based testing to thoughtful systems of assessment that use multiple measures to inform student progress against learning goals

Next steps

To increase the efficacy of student-directed learning, we need to change the dialogue about assessment from event-and pressure-based testing to thoughtful systems of assessment that use multiple measures to inform student progress against learning goals. Our view of learning should no longer be curriculum-, instruction-, and assessment-driven but student-driven. Educators, online curriculum providers, and technology developers need to continue enhancing instructional content and technology capabilities to support immersive and project-based learning environments and help students build portfolios of their learning. Not least, teachers need expanded professional learning opportunities to use assessments and data as integral components of teaching.

The article is based on The Future of Educational Assessment white paper.

© Cognia Inc.

This article may be republished or reproduced in accordance with The Source Copyright Policy.

The information in this article is given to the reader with the understanding that neither the author nor Cognia is in engaged in rendering any legal or business advice to the user or general public. The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this article belong solely to the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Cognia, the author’s employer, organization, or other group or individual.