Education leaders are beginning to expand their school improvement portfolio to include crucial issues—such as culture, climate, emotional intelligence, grit, perseverance and student engagement—that typically have been overlooked in measures of school performance.

Measuring Student Engagement: Why it Matters, How it Works

These crucial areas have matured well beyond theory and provided new models, tools, and evidence to support student achievement. These resources can be used to make changes in schools that research says are correlated with higher performance when properly developed. For example, the ability to analyze levels of student engagement can provide key insights into the success of an initiative, curricula adoption, or program by allowing administrators to see engagement trends and then to adjust their approach throughout the implementation. If students are not more engaged as a result of an initiative, it is almost certain that outcomes will fail to realize their anticipated potential.

The Source contributing editor Sheppard Ranbom interviewed Cognia’s Chief Solutions Officer, Martin Borg, to learn more about the importance and urgency of improving student engagement, how it is measured, how schools and districts use the results, and other key findings from Cognia’s research.

Q. How do you define and measure student engagement?

A. The dictionary definition, from the Glossary of Education Reform, defines engagement as “the degree of attention, curiosity, interest, optimism and passion that students show when they are learning or being taught…” Highly engaged students choose to provide attention, time, and passion to activities that they see as valuable, around topics they see as personally meaningful.

A definition like this is descriptive, but engagement is not simply a matter of “I know it when I see it.” Engagement is something that we can measure across three overlapping, yet specific, dimensions or domains. The first dimension is behavioral; we can determine a student’s participation in the life of the school, including conduct and effort. The second dimension is cognitive—how a student approaches academic tasks and promotes self-learning. And third is the emotional dimension that relates to a student’s feelings about school, staff, and peers.

Using this kind of framework allowed us to design student surveys that probes within and across these three domains. With these surveys. we can also learn more about how different dimensions of engagement play out in school as students develop.

Q. Why is addressing student engagement so important?

A. We know from research that increased levels of student engagement can improve almost every aspect of the educational process. Higher levels of student engagement have been shown to improve test results and graduation rates, reduce disruptive classroom behaviors, and alleviate boredom or feelings of alienation. Lower levels of engagement lead to less transference of skills and weaker understanding of material. Education researcher Bob Marzano, in writing about the highly engaged classroom, puts it this way: “If students are not engaged, there is little, if any, chance that they will learn what is being addressed in class.”

But there are other important reasons engagement matters. Researchers note that students learn best when they find personal meaning and value in what they learn. This helps them doggedly persist in learning, even when the work gets hard. This kind of engagement is far better for students than activities from which students feel disconnected. Connected and engaged learning not only creates transferable skills and alleviates boredom, it also develops the motivation and skills to address the challenges we must, as a global community, solve in the near future.

Beyond school, the nature of work is changing. Employers increasingly value workers who are motivated, take initiative, solve problems, and can think for themselves. This isn’t just about having a happy workplace; it’s about the bottom line. Research from Gallup shows that organizations and teams with higher employee engagement and lower active disengagement perform at higher levels. Gallup also found that organizations that are the best at engaging their employees achieve earnings-per-share growth that is more than four times that of their competitors.

Addressing student engagement drives business now and into the future. Experts worry that in the future, employees who value routine, other-directed work, will be increasingly competing—as more and more formerly “human-only tasks” fall within the purview of technology. According to the McKinsey Global Institute, by 2030 automation could take away up to 30 percent of the jobs that workers do right now—a total of about 800 million jobs, leaving opportunities for only those who are fully invested to find decent work.

Q. Has the recent history of school reform helped create more compliant students who won’t thrive in the emerging economy?

A. The short answer is that No Child Left Behind-type reform efforts focused national attention on gaps in student learning by using standardized tests to measure student outcomes. To the extent that students were told they needed to learn, “because it is on the test,” we reinforced compliant behavior and may have missed the opportunity to discover and utilize students’ own interests as motivators. To thrive in our emerging economy, successful employees will need to “own” their projects and pay attention to the skills associated with higher levels of cognitive engagement, like the ability to transfer learnings to solve problems that may not even exist yet.

Q. How does measuring engagement help educators improve learning and the learning environment for every student?

A. Survey findings can help educators target interventions appropriate to the developmental levels of students and to entire school systems. By understanding what is happening with students across these domains, we can begin to tease out areas for improvement. For example, we have found that when elementary students reported disengagement in two of the three domains, one of them was always the emotional domain. That tells us something about where we need to start.

Q. How do students at different levels of engagement differ?

A. Think about people who need exercise and go to a gym to get in shape. Everyone knows that exercise is good for you and can improve your life. But people take to it differently. There are those who are intrinsically motivated to regularly work out and try new things on their own. But there are also people who really rely on a trainer or a rigid routine. They are compliant. They follow orders or stick to step-by-step drills and never feel invested or immersed in what they do. Then there are those who are disengaged. They find excuses not to work out or barely go through the motions, pretending to be involved. Some just refuse to do the work.

The same holds true with schooling. We describe three types of engagement: Committed, Compliant, and Disengaged. Committed students who are highly engaged find meaning in the task. They are willing to spend their time improving on a work product not to please the teacher, but to meet their own standards. They often go beyond memorization to understand deeper concepts that can in turn be transferred to other subjects or models. They are intrinsically motivated, demonstrate a sense of ownership and drive, and have the ability to understand deeper connections and stick to the task when it gets most difficult.

The students who are most invested are often leaders who consistently deliver stellar work and exceed expectations. They also look for connections and strive for a conceptual understanding of the task at hand. They tend to persevere thorough difficult tasks and see challenges as opportunities.

Then there are students who are really immersed but not as fully invested. They also turn in stellar work, retain most of what they learn, and have a deep conceptual understanding. They connect with what they learn and apply it to their lives, and they see the value of what they are learning and how it will affect their future.

These are the kinds of engagement that we want to see. By contrast, a large proportion of students in schools we have studied are just trying to get by with the least amount of work or interest. Compliant students want to know what you want them to do, and they do it. There are no real behavior issues or real inspiration. Some that researchers categorize as strategically compliant allocate just enough time and effort to get a specific result or a certain grade on a particular test. They will work until the reward is achieved and then stop. Others are ritually compliant. They respond to direct teacher supervision; they do what must be done to stay under the radar, and little else. They are just going through the motions and are easily distracted or discouraged.

Disengaged students do little work. Part of this group will demonstrate ritual behavior to conceal their lack of involvement. Students who are ritually disengaged might sleep in class with their eyes wide open or smile from time to time. Students who are openly rebellious and disengaged refuse to comply with the requirements of the task or may cheat or do other work in place of what is expected.

Q. What proportion of students are committed, compliant, and disengaged?

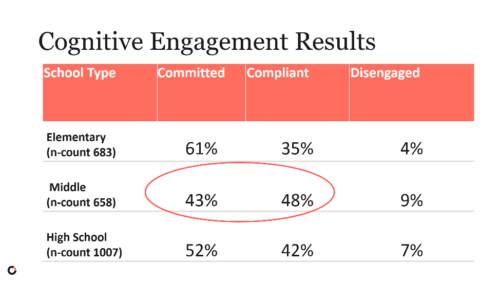

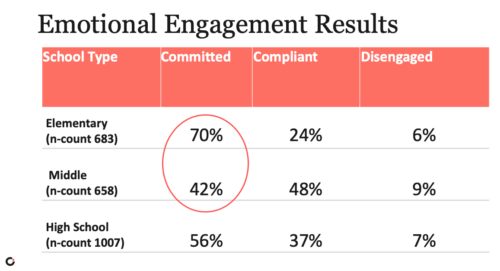

A. Overall, the majority of students feel “committed.” However, in middle school, the number of “compliant” students exceeds “committed” ones in the cognitive and emotional domains.

However, our research also has identified some mixed trends, particularly as students get older.

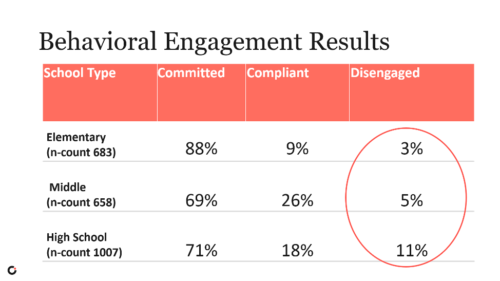

Behavioral disengagement. While the majority of students report to be behaviorally “committed”—that is, joining teams and participating fully in the life of the school, it is interesting to note as shown below that the levels of disengaged students increase in high school, and we suspect the numbers would be higher if we were to account for dropouts. There is some evidence that lower levels of behavioral engagement in the upper elementary grades and middle school are leading indicators of predicting students who drop out of high school. This evidence is in the literature and not an outcome of our research.

Cognitive engagement. The levels of cognitive commitment, show below, are troubling: Cognitive engagement is where we hope to see students actively engaged to their own learning and developing the interest and self-regulating skills needed to be lifetime learners.

The Committed designation is also where we begin to see students developing transferable skills and the ability to learn independently. Students in the highest levels here also exhibit intrinsic motivation.

Emotional engagement. The drop in committed students from elementary school to middle school, shown below, might indicate that as students get older, they are better able to engage cognitively. The drop in emotional engagement might just be a reflection that the older students become, the less willing they are to engage just because of the relationship with the teacher, and we would hope for an increase in cognitive engagement. However, our data do not support these conclusions, as committed levels of cognitive engagement also fall as students enter middle school.

Q. Compliance seems as undesirable as disengagement. But don’t schools typically reward students for falling in line?

A. Well, compliant students are doing the work, and learning what is asked of them, while disengaged students are doing their best to avoid the work altogether. So compliance is preferable to disengagement. However, as a teacher, I did not always recognize the difference between committed or compliant behavior. Students sitting in seats with the homework completed and minimally participating in class seemed to be a “win.” Also, sometimes teachers are grateful for compliance because having children come back with their homework completed can be a small miracle given the challenges many face in their lives. The main problem with an over-reliance on compliance is that it may limit a teacher’s or a student’s own expectations of what they can achieve.

As important, without fully engaging with the underlying relationships of a concept, students may not be able to transfer these principles to new work or tasks and instead find themselves having to memorize a “new” set of ideas. They may lack the ability to quickly employ higher-level cognitive skills to new problems and fall back on inefficient “brute force” memorization to get the work done.

The problem is that compliant students not only invest less in their own learning, but the types of classroom motivation, extrinsic v. intrinsic, are at odds with the types of skills and behaviors most in demand from today’s employers and employment opportunities in the future.

For so many reasons, school and district leaders need to develop ways to help teachers get students connected to their own internal motivations, and to a vision of what it can be like to live fully engaged in whatever they do. This is one of the best things teachers can do for students.

© Cognia Inc.

This article may be republished or reproduced in accordance with The Source Copyright Policy.

The information in this article is given to the reader with the understanding that neither the author nor Cognia is in engaged in rendering any legal or business advice to the user or general public. The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this article belong solely to the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Cognia, the author’s employer, organization, or other group or individual.