Every day across the country, students encounter wide and troubling variations in their school experiences. Some schools and school systems thrive by applying the latest learning science research and using evolving technologies. Others, frequently located in communities of poverty or concentrated minority demographics, sort students and pass them along using strategies and tools developed 100 years ago.

It is time to reorient the entire teaching and learning enterprise to focus on what matters most: ensuring that all children have access to rigorous, relevant, and powerful learning experiences led by caring, competent, and qualified teachers every year they are in school.

Our path to improvement has focused too much on standards and accountability but not enough on equity and the conditions of teaching and learning in schools. Further, while we know that effective teachers are critical to the academic and personal success of students, we have not mustered the collective will to demand recruitment, preparation, induction, retention, and professional support practices that will produce these teachers. We let individuals become teachers with little training and continue to place the least experienced teachers in our nation’s most challenging classrooms.

As a result, we continue to struggle with an expensive, uneven and inequitable patchwork of learning that many refer to as a “non-system” of education. Supporting all of today’s students as they strive to be successful, productive and informed citizens is one of the most important issues facing our country today.

The goal of the National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future (NCTAF) is to address these equity issues by working with states to transform teaching and learning environments to serve all students well. The Commission recently released the report What Matters Now: A New Compact for Teaching and Learning. Co-chaired by former U.S. Secretary of Education Richard Riley and Ted Sanders, a former president of the Education Commission of the States, the Commission spent 18 months investigating school systems and student performance to identify the conditions and vision necessary to create a new kind of education system that supports deeper learning for every student.

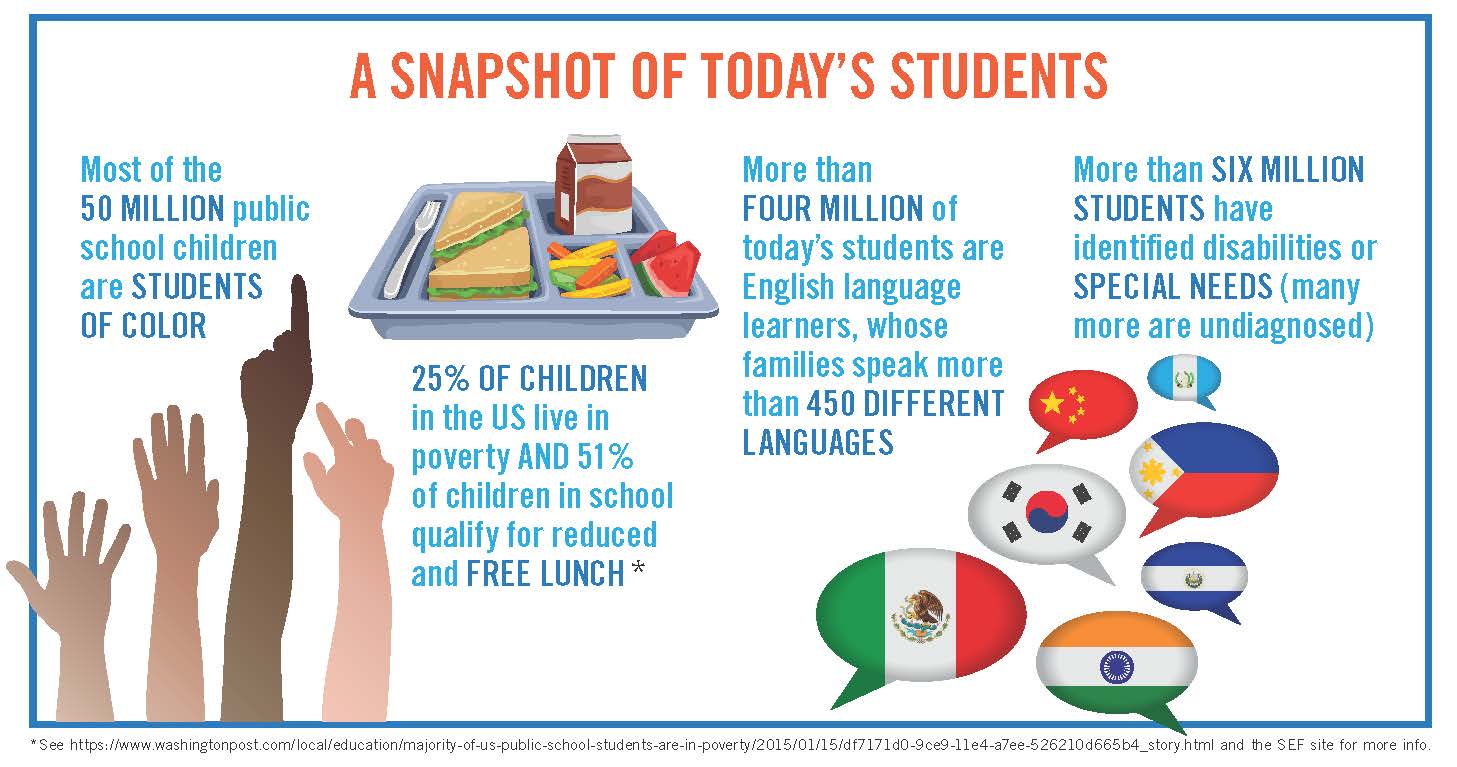

*Graphic courtesy of the National Commission on Teaching & America’s future www.nctaf.org and its report What Matters Now: A New Compact for Teaching and Learning available here.

*Graphic courtesy of the National Commission on Teaching & America’s future www.nctaf.org and its report What Matters Now: A New Compact for Teaching and Learning available here.

The Challenges We Face

As part of its analysis, the Commission—which is comprised of 19 prominent educators and leaders from different sectors of society—compiled alarming evidence of ongoing inequities, including the following:

- Access to courses. Recent statistics from the U.S. Department of Education show that only 57 percent of Black high school students and 65 percent of Hispanic high school students have access to the full range of courses necessary to succeed in college and careers, compared to 71 percent of White students.[1]

- Early childhood education. Despite decades of research showing the long-term benefit of early education interventions, only 41 percent of children in low-income communities are enrolled in preschool, compared with 61 percent of children in wealthier communities.[2]

- Students living in poverty. Today nearly one in four American students live in conditions of poverty—a rate higher than that of any other advanced industrial nation in Europe, North America, and Asia. This percentage is even higher for students of color.[3] More than half of all students in American schools are low-income and qualify for free or reduced-price school lunches.[4]

- Access to quality teaching. A recent study finds that students in high-poverty districts are twice as likely to be taught by teachers with temporary alternative licenses as students in low-poverty districts. This includes both rural and urban high-poverty schools.[5] Nearly seven percent of the country’s Black students — totaling more than half a million children — attend schools where at least one out of every five teachers does not meet state certification requirements. Black students are more than four times as likely and Hispanic students are twice as likely as White students to attend these schools.[6]

- By every measure of teacher qualifications — including SAT scores, GPA, licensing, major, selectivity of undergraduate institution, experience, and others—high-poverty students and students of color are least likely to be taught by well-prepared, profession-ready teachers. The reality is that in order to meet shortages, states and the federal government allow people to teach who have not yet completed their training or demonstrated their abilities. The fact that these teachers are concentrated in high-need schools and districts that do not have the resources to remediate this lack of training exacerbates the problem.

- Achievement gaps. The current education system simply does not work for millions of low-income students. Over the past 25 years, the achievement gap between high- and low-income students has increased by 30-40 percent.[7] These gaps begin before children start kindergarten and widen throughout their school years. In addition to missing pre-school opportunities, low-income students are less likely to receive adequate and preventative physical and mental health care services, and less likely to experience structured or unstructured out-of-school learning experiences.[8] Students living in low-income circumstances also are more likely to experience food insecurity, homelessness, childhood trauma and violence.[9]

- Unprepared teachers. The 2,100 teacher preparation programs train nearly 500,000 candidates through graduate and undergraduate coursework, alternative certification initiatives, and an array of face-to-face, online, and blended options represent amazing variation. Some programs require intensive coursework and classroom experiences; others do not. This uneven preparation suggests why, in a recent survey, 62 percent of new teachers said they felt unprepared for the classroom.[10]

It does not have to be this way. Across the nation, dozens of states have taken action to address many of these problems, and we know more than we ever have about how students and teachers learn and develop. We have research-based evidence about the importance of investing in the human factor—the motivation of students and teachers—to increase results. The evidence shows that we must engage students’ social and emotional learning in order to truly engage them in mastering academic content. Meanwhile, our teachers need time, opportunities to collaborate with their colleagues, and relevant supports in order to effectively explore and incorporate this knowledge into their teaching practice. In order to do this, we must implement systemic changes across the entire teaching career continuum.

Redesigning Teaching and Learning

What Matters Now calls for transforming our entire education enterprise by establishing teaching and learning environments that inspire all students and teachers. It lays out a vision and Commission recommendations—targeted especially at state and local policy makers—based on examples of states, districts, schools, and teachers working to modernize and personalize learning for all students.

For example, in an increasing number of schools, students are active learners who initiate what they study, learn to ask questions, and uncover answers for themselves. They demonstrate mastery of subject matter by writing papers and proposals, making presentations, and by organizing and managing events in which they take a lead role. These are skills essential for future learning and careers.

In these schools, learning is more meaningful and relevant than in the traditional structure of classrooms. Students study interdisciplinary areas of knowledge—science, history, math, music and literature—by doing authentic projects such as ones that examine the relationship between climate change and natural disasters or come up with new public health strategies to address chronic diseases.

Guided by their teachers and the principal, students in these schools become progressively more involved in the things that matter to them. Extending their learning, students may work with a biotech firm or medical lab to conduct real research, or develop an exhibit in a local museum. Teachers become facilitators of these extended relevant learning experiences, expanding their own experiences and networks at the same time.

Such experiences for students happen because the teachers themselves are inspired. The schools have established a commitment to making teaching a collective effort. Teachers’ and principals’ work is dynamic and collaborative, and their professional relationships extend beyond the walls of their classroom and their school, including across the globe.

The Way Forward

The Commission’s call for transformation seeks to move the U.S. education system out of the 20th century industrial model of command and control and into a new model that is more about innovation, collaboration, and deeper learning. One commissioner, Harvard University’s Jal Mehta, observes that under the current system, the federal government sets requirements for what states do, states control what happens in districts, districts control what happens in classrooms, and teachers control students. The Commission proposes to flip this dynamic so that education leaders at the school level are driving the way education is structured in order to address the unique needs of an increasingly diverse student population.

The Commission report identifies numerous places where schools and districts are being transformed and recommends strategies for states and localities to adopt that, taken together, can transform teaching, learning and our nation’s schools. The strategies include:

- Enter into a new compact with teachers. At the heart of learning is great teaching. The Commission is calling for dramatic changes in how we support and organize teaching. It urges policymakers to establish and broadly communicate a new compact with teachers who acknowledge the potential of teachers to drive improvement if given support and resources, treats teachers as life-long learners, and increases teachers’ access to capacity building and tools required to improve student learning. It calls for states and districts to prioritize greater collaboration and continuous improvement for both students and teachers, support the development of structures for teacher leaders who take an active voice in school and district decision making, and to formalize educator-led bodies, such as educator standards boards or advisory councils, as part of the policymaking process.

- Establish a statewide Commission on Teaching, Learning and the State’s Future. The shifts and supports required to support a new teaching and learning system are complex, interrelated and require time and investment. Therefore, the Commission urges every state to have multi-stakeholder commissions to assess whether they are meeting the needs of today’s—and tomorrow’s—students. State commissions need to create an asset map and needs assessment of policies and practices with regard to teacher recruitment, preparation, retention and practice as well as expectations for student learning. It calls for the development of a strategic plan for improvement based on local assets, standards, and priorities. The Commission should reexamine state learning standards and how they are translated into rubrics to govern the teaching and learning process, and review statewide learning assessments and accountability systems.

- Track whether all schools are “organized for success.” No one factor ensures student and teacher learning. Rather states should establish (or codify existing) indicators of whether schools are organized to maximize access to learning opportunities. Factors include:

- Familiarity with, and ability to use research on how students learn, what effective teacher practice looks like, assessment literacy, cultural competencies and effective professional learning strategies

- Support and capacity building for teachers to make shifts toward improved student outcomes for all students

- Technology employed to personalize learning, broaden access to deeper learning experiences, and support collaboration for both students and teachers

- A demonstrated commitment to recruiting, retaining, and developing great teachers

- Protected time—at least 15 percent weekly—for professional collaboration such as shared assessment work, co-teaching, and observations of colleagues’ classrooms

- A system of shared accountability that is focused on improvement

- Meaningful engagement of family and community through projects, workplace partnerships

- A commitment to collecting and using data and information from parent and community feedback

- Reboot teacher preparation, induction, and professional learning. To ensure that more teacher candidates complete school ready to teach in the new system, the Commission calls for teacher preparation to require a year of clinical experience with coursework focused on social-emotional as well as academic learning, and grounded in culturally knowledgeable and responsive practices. The clinical component should conclude with performance assessments as a means to reliably ensure that beginning teachers are competent to lead a classroom. The Commission calls on states to support all new teachers with multi-year induction and high-quality mentoring. Further, to foster life-long professional growth, the Commission urges education leaders to evaluate ALL professional learning for responsiveness and effectiveness. The design of these programs should be done at the school level with significant teacher input and a focus on real day-to-day instructional issues.

The Time Is Now

We know how to design and develop schools that personalize learning for students and encourage teachers to develop into accomplished practitioners and leaders, but as a country, we have not been embracing these strategies for all students. The passage of the new federal Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) offers an opportunity to change all that – to envision the teaching and learning system differently, use funding in new ways, and think differently about how to measure successes. States across the nation have the chance to introduce policy that is not dictated by politics, but rather is determined by evidence of success and the professional judgment of educators.

If we really want all students to succeed, we need to address inequities in learning. It is time to think differently about how schools are organized, how accountability is structured, and how teachers are supported—all so that teachers can learn, lead, and be successful with the diverse population of students they are charged to educate.

[1] U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights. (2014, March 21). Civil rights data collection: Data snapshot (College and Career Readiness). Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/crdc-college-and-career-readiness-snapshot.pdf.

[2] U.S. Census Bureau. (2012, October). Current population survey, Table 3 [Data file]. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/hhes/school/data/ cps/2012/tables.html.

[3] Burns, D. & Darling-Hammond, L., (2014). Teaching Around the World: What Can TALIS Tell Us? Stanford, CA: Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education.

[4] Suitts, S. (2015). A new majority research bulletin: Low income students now a majority in the nation’s public schools. Atlanta, GA: Southern Education Foundation.

[5] U.S. Department of Education Office of Planning, Evaluation and Policy. (2015). Highly qualified teachers enrolled in programs providing alternative routes to teacher certification or licensure. Washington, D.C.: Author.

[6] U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights. (2014). Civil rights data collection: Teacher equity. Washington, D.C.: Author.

[7] Reardon, S.F. (2011). The widening socioeconomic status achievement gap: New evidence and possible explanations. In R. J. Murnane & G. J. Duncan (Eds.), Whither Opportunity? Rising Inequality, Schools, and Children’s Life Chances. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

[8] Loeb, S. & Bassok, D. (2007). Early childhood and the achievement gap. In H.F. Ladd & E.B. Fiske (Eds.) Handbook of Research in Education Finance and Policy. London: Routledge.

[9] American Psychological Association. (2016). Children, youth, families and socioeconomic status. Washington, D.C.: Author.

[10] Levine, A. (2006). Educating school teachers. Princeton, NJ: The Woodrow Wilson National Fellowship Foundation.

© Cognia Inc.

This article may be republished or reproduced in accordance with The Source Copyright Policy.

The information in this article is given to the reader with the understanding that neither the author nor Cognia is in engaged in rendering any legal or business advice to the user or general public. The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this article belong solely to the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Cognia, the author’s employer, organization, or other group or individual.