Educational leaders are under pressure to improve school performance through effective teaching and learning. Legislative entities, policymakers, and educational leaders increasingly focus their attention on teacher professional development (TPD) for improving teacher knowledge, skills, and efficacy while simultaneously improving student learning outcomes (Broad, 2015; McComb & Eather, 2017; Moghtadaie & Taji, 2018; Pittman & Lawdis, 2017).

While the responsibility of ensuring teacher participation in professional development often falls on the principal as the educational and instructional leader of the school (Vogel, 2018), principals must plan TPD initiatives, set expectations for implementation, and evaluate implementation results (Celeste, 2016) in addition to a multitude of other responsibilities and requirements that tax principals’ schedules and workload.

With so many obligations on a principal’s time, how can principals integrate professional learning activities efficiently into school programming and provide a meaningful experience that enhances teaching and learning?

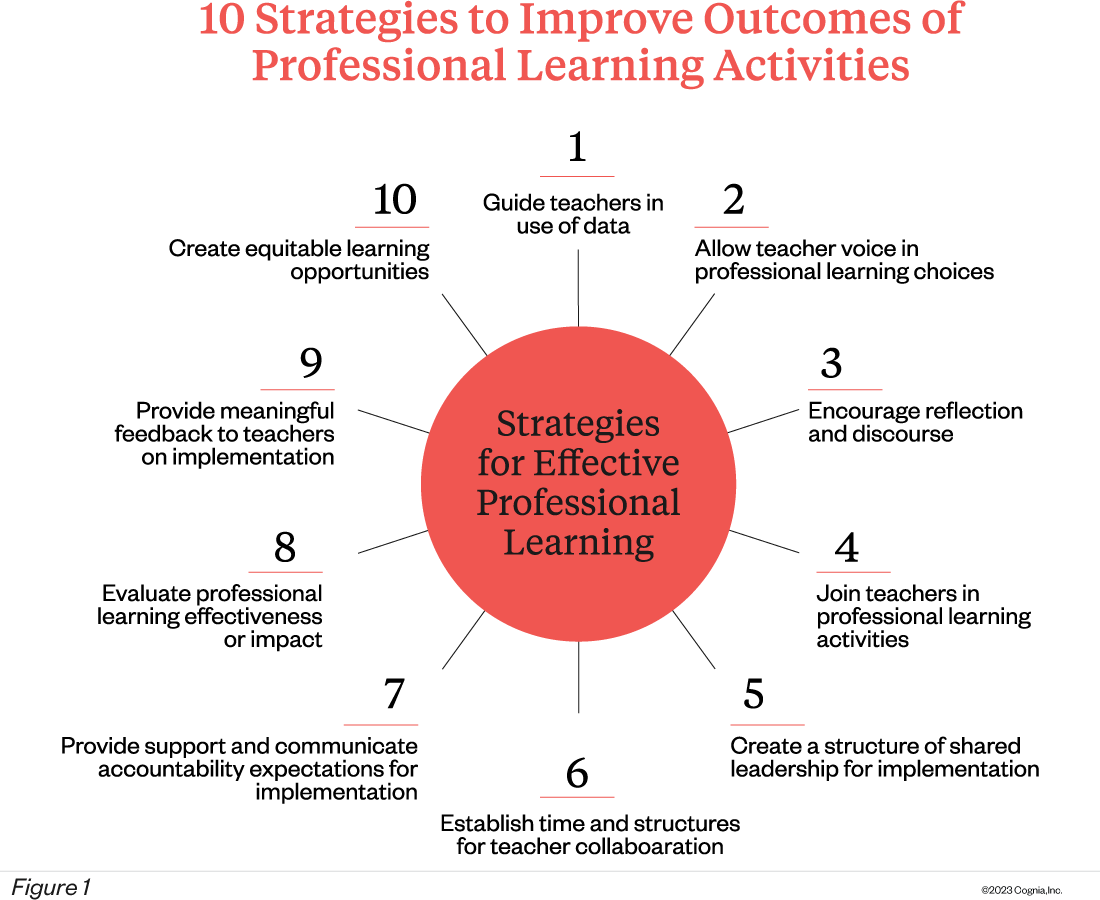

Darling-Hammond (2015) expresses the importance of meaningful professional growth in her statement, “We cannot make major headway in raising student performance and closing the achievement gap until we make progress in closing the teaching gap” (p. 4). Adult learning theory or andragogy (Knowles et al., 2012) are critical considerations for enhancing the professional learning experiences of teachers. Knowles et al. (2012) reiterate the importance of meeting the adult’s need for involvement in the planning and evaluation of their instruction, using individual past professional experiences to determine learning activities, articulating the relevance of professional learning content’s impact on improving current practices, and having a problem-centered focus to the learning. Additional consideration should include studies focused on the teacher’s perspective. Teachers report several elements that are most desirous and effective in improving their willingness to participate meaningfully in professional learning activities and implement learned strategies to improve instructional practices. Principals can implement strategies aligned to adult learning theory (Figure 1. Ten Research-based strategies to improve outcomes of professional learning activities) and to enhance the experience for teachers and increase the likelihood of implementation with fidelity.

When professional learning is viewed as a comprehensive and collaborative process, the principal can facilitate and guide professional learning activity much more effectively and efficiently as all instructional staff can share in the planning, implementing, supporting, and evaluating. Principals who establish collaborative structures for professional learning free up their time to tend to other tasks.

Professional learning is effective in closing the teaching gap when it is equitable and attainable by all teachers regardless of geographic location and readiness levels (Covay Minor et al., 2016; Darling-Hammond, 2015; Ringler et al., 2013). In terms of strategies, when planning, principals who engage teachers in making collaborative data-informed decisions regarding the choice of professional learning content and activities (Lange, et al., 2012) are likely to experience more buy-in and active participation. Upon implementation, principals who make improvement evidence and data accessible to teachers and reserve time for collaboration for analyzing data with teachers, grant teachers opportunities to generate valuable insight on the topics, content, and type of professional development needed.

The implementation of learned strategies should be monitored and evaluated (Fourie, 2018; Martin, & González, 2017). The tasks associated with monitoring such as conducting classroom observations, leading collaborative discussions about implementation challenges and successes; gaining feedback on the effectiveness of the learned strategies (Ringler et al., 2013); providing time and support for implementation (Martin & González, 2017; Ringler et al., 2013); and, providing meaningful feedback to teachers about implementation (Darling-Hammond, 2015; Ringler et al.,2013), are too labor intensive for the principal or instructional leader to manage on their own. Shared leadership is an opportunity to improve the learning culture and increase the support for teachers implementing learned strategies in the classroom. Meaningful feedback offers an additional layer of support for teachers to persist in implementation that improves instructional practices. An important aspect for teachers is that the principal joins them in each of the professional learning activities (Ringler et al., 2013). Teachers need to know they are supported by leadership in each learning opportunity. When principals, join, they become a fellow learner who is more equipped to provide feedback and guide discussions for the next steps.

Teachers need to know they are supported by leadership in each learning opportunity. When principals, join, they become a fellow learner who is more equipped to provide feedback and guide discussions for the next steps.

In a recent study entitled the Effects of Monitoring and Evaluating Schoolwide Professional Development Implementation (Reeves, 2021), principals who participated felt most successful when they actively participated in professional learning and modeled a positive attitude, gave teachers a voice in choosing content, remained focused on student learning, and offered support and feedback to the teachers. Professional learning plays an important part in educational policy and practice. As the instructional leader, the principal guides all professional development activities. Although a principal faces many challenges and may have limited time in their day-to-day activity, their role in improving teaching and learning should not be ignored. Principals must find a way to prioritize tasks that improve outcomes for all learners – students or adults. Learning from the experiences of other leaders, principals can differentiate which behaviors are desirable, which are ineffective, and which behaviors could be tried to improve overall organizational results.

One Principal’s Journey

As an example of research in action, Jill Grabert, principal of St. Cletus School, shares her personal experiences in implementing successful professional learning processes after changing their model of professional development. In this small Catholic school with limited human resources, participation had previously been a “one and done” model where teachers participate with little or no follow-up activity. Teachers were attending grade or subject specific professional development without any substantial over all school improvement. Using a formal classroom observation process, , Grabert discovered that teachers were more compliant than engaged.

In response to this realization, Grabert started incorporating whole-school-engagement professional learning and used classroom observations to monitor implementation and progress. Once this happened, Grabert purposefully grouped teachers for collaboration. Expectations for implementation were set, communicated, and monitored. Grabert noted that as the lone administrator on campus, she needed assistance with professional development planning and implementation and elicited the help of a consultant.

Growth mindset became the focus for a new schoolwide professional learning plan for three years. Using a variety of book studies and resources, the first year focused on faculty and staff learning and understanding what Growth Mindset is and what it is not. Professional learning was integrated into the school’s schedule for early dismissal days where staff worked through two of the 12 concepts in The Growth Mindset Coach (Brock and Hudley, 2016). Each month after the sessions with the teachers, there was either a day for goal setting during teacher planning time or informal observations to see that implementation was taking place.

Teachers need time to learn, develop, and master new strategies. Further, they need clear expectations for implementation and monitoring to ensure implementation with fidelity

With a continued focus of growth mindset for year two, teachers who were slow to adopt the concept were pushed during the goal setting meetings to implement and have visuals hung in the classroom to assist students and teachers with gaining proficiency in the use of growth mindset. Year three goals included a complete implementation for growth mindset. During this year, growth mindset became embedded into the practice of all teachers. In fact, a new teacher commented through the accreditation engagement review interview that growth mindset is the way things are done at the school. To sustain such embeddedness, year four included growth mindset refresher discussions during teacher learning sessions. A new focus for professional learning has morphed into John Hattie’s concept of Visible Learning—A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Discovery walks and student and teacher survey results reinforced that the system of professional learning for improvement is both beneficial and attainable. Grabert explains that the main lessons learned, are that “teachers need time to learn, develop, and master new strategies. Further, they need clear expectations for implementation and monitoring to ensure implementation with fidelity.”

Conclusion

Professional learning plays an important part in educational policy and practice. As the instructional leader, the principal guides all professional development activities. Although a principal faces many challenges and may have limited time in their day-to-day activities, their role in improving teaching and learning should not be ignored. Principals must find a way to prioritize tasks that improve outcomes for all learners–students and adults. Learning from the experiences of other leaders, principals can differentiate which behaviors are desirable, which are ineffective, and which behaviors can improve overall organizational results.

*Note: As part of the Cognia Learning Community, network members have access to a Community of Practice discussion group in Cognia Home.

Resources

Brock, Annie and Hundley, Heather (2016) The Growth Mindset Coach: A Teacher’s Month-by-Month Handbook for Empowering Students to Achieve, Berkley, CA, Ulysses Press, 2016.

Hattie, John A.C., Visible Learning—A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement, New York, Rutledge, 2009.

References

Broad, J. H. (2015). So many worlds, so much to do: Identifying barriers to engagement with continued professional development for teachers in the further education and training sector. London Review of Education, 13(1), 16–30. https://doi.org/10.18546/lre.13.1.03

Covay Minor, E., Desimone, L., Caines Lee, J., & Hochberg, E. D. (2016). Insights on How to Shape Teacher Learning Policy: The Role of Teacher Content Knowledge in Explaining Differential Effects of Professional Development. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 24(61). https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.24.2365

Darling-Hammond, L. (2015). Want to Close the Achievement Gap? Close the Teaching Gap. American Educator, 38(4), 14–18. https://www.aft.org/sites/default/files/darling-hammond.pdf

Fourie, E. (2018). The impact of school principals on implementing effective teaching and learning practices. The International Journal of Educational Management, 32(6), 1056–1069. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-08-2017-0197

Hao, L., Yunhuo, C., & Wenye, Z. (2018). Relationships between student engagement and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 46(3), 517-528. https://doi.org/10.2224/spb.7054

Knowles, M. S., Holton, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (2012). The adult learner. The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Seventh edition. Routledge.

Lange, C., Range, B., & Welsh, K. (2012). Conditions for Effective Data Use to Improve Schools: Recommendations for School Leaders. International Journal of Educational Leadership Preparation, 7(3). https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ997478

Martin, T. S., & González, G. (2017, October 1). Teacher Perceptions about Value and Influence of Professional Development. North American Chapter of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education, p. 39. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED581328.pdf

Mukan, N., Fuchyla, O., & Ihnatiuk, H. (2017). Constructivist approach in a paradigm of public school teachers’ professional development in Great Britain, Canada, the USA. Comparative Professional Pedagogy, 7(2), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1515/rpp-2017-0016

National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance. (2016, November). Does content-focused teacher professional development work? (Issue Brief). Washington DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Educational Sciences. Retrieved from https://ies.ed.gov/ncee/pubs/20174010/pdf/20174010.pdf

Ringler, M. C., O’Neal, D., Rawls, J., & Cumiskey, S. (2013). The Role of School Leaders in Teacher Leadership Development. The Rural Educator, 35(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.35608/ruraled.v35i1.363

Reeves, N. (2021). Effects of Monitoring and Evaluating Schoolwide Professional Development Implementation: A Phenomenological Study [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. American College of Education.

Learn more about our commitment to Catholic Schools.

© Cognia Inc.

This article may be republished or reproduced in accordance with The Source Copyright Policy.

The information in this article is given to the reader with the understanding that neither the author nor Cognia is in engaged in rendering any legal or business advice to the user or general public. The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this article belong solely to the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Cognia, the author’s employer, organization, or other group or individual.