First, there is no consensus about poverty’s causation. Virtually all disciplines move through three phases: classification, where things are named; correlation, an explanation of how things work together; and causation, which explains what creates a phenomenon. Regarding the latter, the field of sociology has four separate, well-researched bases[ii] about what causes poverty and creates class in the United States.

The first research base is about individual choices and behaviors; the second is centered on community conditions, including resources, jobs, social capital, etc.; the third involves exploitation (predators, racism, sexism, etc.); and the fourth pertains to political and economic systems and structures.

Four Causes of Poverty and Class

|

INDIVIDUAL BEHAVIORS AND CIRCUMSTANCES |

COMMUNITY CONDITIONS |

EXPLOITATION |

POLITICAL/ECONOMIC STRUCTURES |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Definition:

|

Definition:

|

Definition:

|

Definition: |

|

Sample topics:

|

Sample topics:

|

Sample topics:

|

Sample topics:

|

Source: Philip E. DeVol, Getting Ahead in a Just-Gettin’-By World[iii]

These research bases have become increasingly politicized in recent years. If you are on the political right, you likely think poverty is caused by the first two research bases: mostly individual behaviors but also community conditions. If you are on the political left, you probably think it’s caused by exploitation and political/economic systems and structures. So legislators argue about causation, or they pass a law based on one cause, and then “the solution” doesn’t work. So they fight some more about causation. The reality is that all four of the aforementioned factors together cause poverty.

The argument about causation has greatly impacted public schools in the area of funding issues. Almost all state legislatures these days are cutting school budgets and, when you listen to the discussions, many times the conversation and blame will go back to one of these causes. Currently, only 40 percent of U.S. households have school-age children. More than half of them are under-resourced households and tend not to vote. The 60 percent of households that do not have school-age children usually vote.

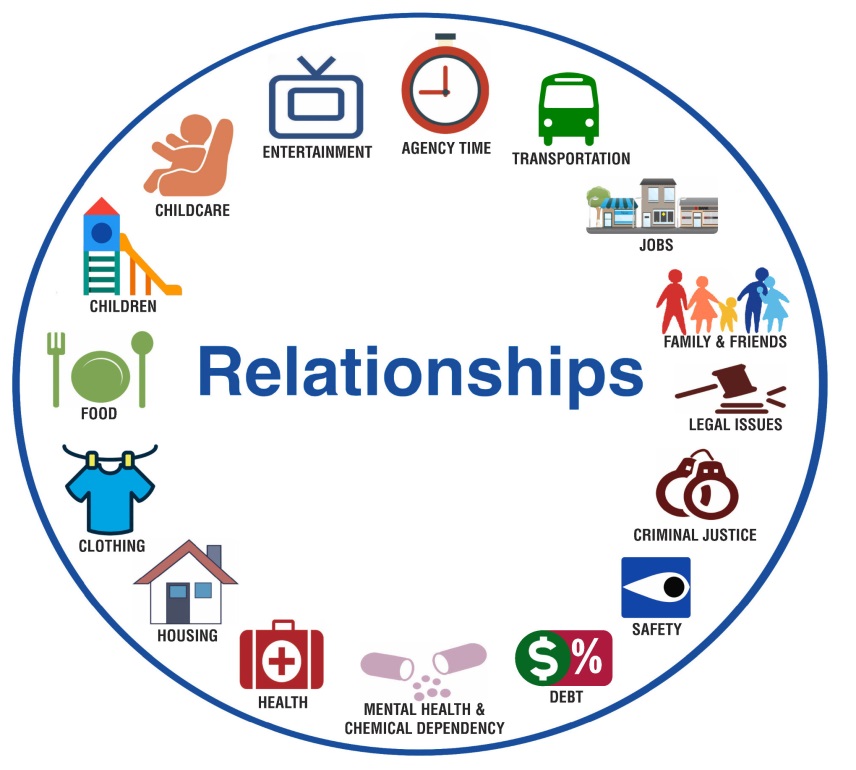

The second issue relevant to the politics of poverty is the relationship between the stability of one’s resources (financial, mental, emotional, relationships, support systems, spiritual, physical, formal register, knowledge of hidden rules)[iv] and how a person uses his/her time. All of us have 24 hours a day. That’s it. So how we spend our time determines what we know. And these days if you want to make a good living, you have to be a part of the knowledge economy, which means you have to be educated.

At aha! Process we have a facilitated program based on the book Getting Ahead in a Just-Gettin’-By World; and 50,000 adults from poverty have completed this program. We believe that adults in poverty are problem solvers. We asked them, as the experts in poverty, to tell us how they spend their time.

This is a compilation of what 300 adults in poverty[v] say they spend their time doing.

My question to you is this: What is on this chart that you do not spend your time doing?

The next chart is what individuals who have mostly stable resources[vi] (i.e., they know they have food every day, they know where they’re going to sleep at night—the middle class) say they spend their time doing.

What do you see in this chart that you didn’t see in the first chart?

The third chart is what people in wealth[vii] say they spend their time doing (top 1% of households in the U.S.—net worth of $7.8 million[viii] or more).

What do you see in this chart that you didn’t see in the other charts?

So what is the point?

The point is that all of these circles are in your state and in your community. They all participate in public education. And for the most part, the people in one circle don’t understand the people in the other circles very well at all. The wealth circle usually controls legislative decisions. The middle circle generally runs the institution of schools. And the circle of poverty sends the most children to public schools. We have three very different realities based on the fact that time is spent very differently, and so the understanding of what is important and how the world works is also very different. The ability to work together to solve a problem such as poverty becomes difficult under these circumstances. Typically, there isn’t much conversation between and among the three circles.

What can we do about it?

To successfully address the issue of poverty and break the cycle, it is very important to use a two-generation approach. The adults and children must be addressed together. At aha! Process we have been doing that through programs called Getting Ahead and Bridges Out of Poverty. But even more important than such programs, it is imperative that resourced individuals in communities understand the reality of poverty—not taking a blame approach or an excuse approach but rather having an accurate picture of reality. To do that requires open communication and conversation.

A friend of mine who is a brilliant strategist and philanthropist said to me:

Ruby, we take students from unstable environments (high mobility, food insecurity, changing households, relationships, unpredictable medical care) and we put them in schools that are constantly changing and unstable (different administrators, a cycle of new teachers, changing laws and tests), and then we wonder why we don’t get better results. I am going to educate the resourced about the reality of being under-resourced because they [the resourced] will help make laws that stabilize schools, institutions, and communities.

References

DeVol, P. E. (2015). Getting ahead in a just-gettin’-by world (3rd rev. ed.). Highlands, TX: aha! Process.

Frank, R. (ed.). CNBC. (2015, September 16). Inside Wealth. Retrieved from http://www.cnbc.com/2015/09/16/top-1-of-harvard-grads-richer-than-americ…

Layton, L. Washington Post (2015, January 16). Majority of U.S. public school students are in poverty. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/education/majority-of-us-public-sch…

Payne, R. K. (2013). A framework for understanding poverty: A cognitive approach (5th rev. ed.). Highlands, TX: aha! Process.

Payne, R. K., DeVol, P. E., & Dreussi-Smith, T. (2009). Bridges out of poverty: Strategies for professionals and communities (4th rev. ed.): Highlands, TX: aha! Process.

Payne, R. K., DeVol, P. E., & Dreussi-Smith, T. (2016). Bridges out of poverty: Training Supplement. Highlands, TX: aha! Process[DS1] .

Citations

[i] L. Layton, Washington Post, Majority of U.S. public school students are in poverty.

[ii] P. E. DeVol, Getting Ahead in a Just-Gettin’-By World, p. 42.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] R. K. Payne, A Framework for Understanding Poverty: A Cognitive Approach, p. 8.

[v] R. K. Payne, P. E. DeVol, & T. Dreussi-Smith, Bridges Out of Poverty: Training Supplement (2016), p. 6.

[vi] Ibid., p. 14.

[vii] Ibid., p. 16.

[viii] R. Frank (ed.), CNBC, Inside Wealth.

© Cognia Inc.

This article may be republished or reproduced in accordance with The Source Copyright Policy.

The information in this article is given to the reader with the understanding that neither the author nor Cognia is in engaged in rendering any legal or business advice to the user or general public. The views, thoughts, and opinions expressed in this article belong solely to the author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Cognia, the author’s employer, organization, or other group or individual.